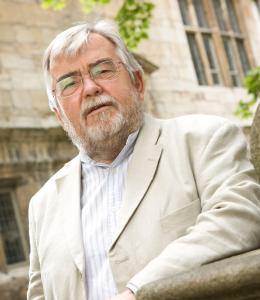

James Walvin is Professor of History Emeritus at the University of York, where he spent most of his career, alongside teaching positions and research fellowships in the USA, the Caribbean and Australia. His publications range widely over the field of modern social history, but most – and most recently – are concerned with the history of slavery. His books include Black and White: The Negro and English Society 1555-1945 (Allen Lane 1973), Black Personalities in the Era of the Slave Trade (Palgrave Macmilan 1983) with Paul Edwards and A World Transformed: Slavery in the Americas and the Rise of Global Power (Robinson and University of California Press 2022). In 2008, he was awarded an OBE for services to scholarship.

What research were you doing during your time at IASH?

My new book, A World Transformed: Slavery in the Americas and the Rise of Global Power, has roots which stretch back to my fellowship at IASH 51 years ago – and beyond. During that Fellowship I wrote Black and White: The Negro and English Society 1555-1945, the first serious academic study of its kind, and the winner of the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize. But equally important, I found myself in the company of a small group of brilliant and generous colleagues: George (Sam) Shepperson, Christopher Fyfe, Ian Duffield and the irrepressible Paul Edwards. Paul and I subsequently wrote Black Personalities in the Era of the Slave Trade, based partly on my time at IASH.

The Fellowship allowed me to mix with and to learn from distinguished scholars – and all were great encouragers of much younger colleagues. It also allowed me to chance my arm in unexplored areas of history, and accumulate research material which has flowed through a number of subsequent books. I also fell in love with the city.

At the time – and it is hard to overstate this – slavery was a minority interest, of little concern to most British academics; Edinburgh was a great exception. Today, slavery is ubiquitous both in academe and in political and social conversation. Few today would deny that slavery occupied a central position in the shaping of modern British history, hence the title of my new book. And hence the current widespread preoccupation with surviving traces of slavery and the British well-being it generated.

How has your research developed in recent years?

In recent years, my research has broadened. I began my publishing career, with Michael Craton, in a study of a single slave plantation in Jamaica: Worthy Park. Today, I try to make sense of African slavery in its global setting. Here, after all, was an institution which not only blighted Africa, enabled the settlement of the Americas and enhanced the well-being of the Western word – but also had consequences for the wider world.

Do you think scholarly discussions of Empire and colonialism have changed since you were at IASH?

What once seemed small noises off-stage have become a deafening clamour: slavery has taken its rightful place as a central issue of wide concern to anyone interested in the development of Western life and well-being since, say, 1600. My own work in helping to make this point was greatly assisted by my Fellowship at IASH 51 years ago.