Reflect on what is habitual! Who could or would wish to begin such reflection? How should one suspect some mystery in what one has always seen, done, or felt? […] Heavy bodies fall, movement is communicated; the stars revolve over our heads, and what subject for wonder, what subject for inquiry could there be in such familiar things!

Pierre Maine de Biran, Introduction to Sur l’influence de l'habitude sur la faculté de penser (1802)

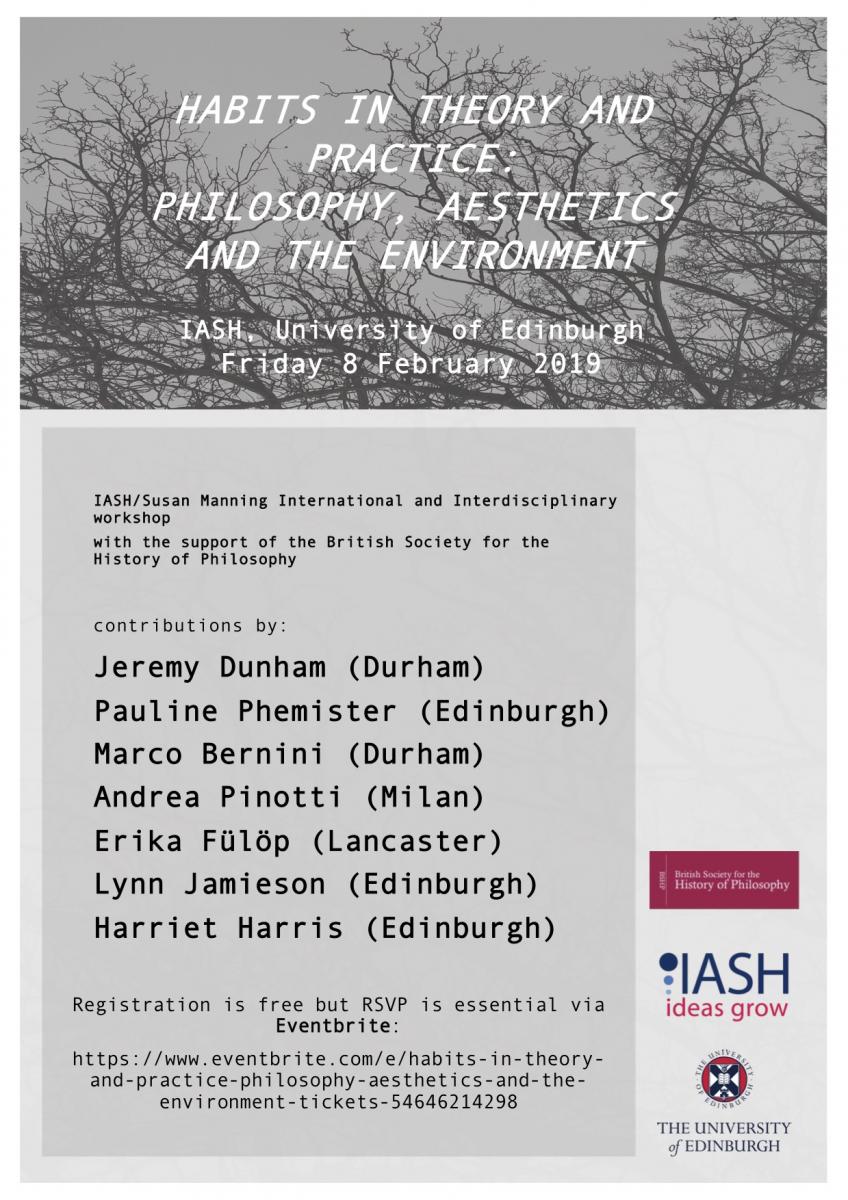

On Friday 8th February 2019, IASH hosted the interdisciplinary workshop Habits in Theory and Practice: Philosophy, Aesthetics and the Environment, supported by IASH as part of our Susan Manning Workshops series, and by the British Society for the History of Philosophy. By bringing together researchers working on habits in academic fields as varied as literary theory, history of philosophy, history of spirituality, environmental studies and sociology of the environment, the workshop aimed to facilitate inter-sectoral and interdisciplinary debate on habits, to foster the exchange of insights and thoughts among researchers with different expertise and backgrounds, and to combine theoretical and practical approaches to the concepts of habit and habitual behaviour. 2018-19 EURIAS Junior Fellow Dr Mariagrazia Portera explains more:

Habits have been a key object of philosophical investigation for centuries, from Aristotle to David Hume, from Hegel to the French spiritualists, from classical Pragmatism to the most recent developments of neo-Pragmatism. Beyond this “strictly” philosophical realm, habits also play a pivotal role in psychology and cognitive sciences (“to have a mind like ours, what is needed are habits like ours”, the philosopher of cognitive sciences Alva Noë argues), in sociology (with Bourdieu’s concept of habitus), in the arts and aesthetic experience (for instance, with Michel Proust’s notion of habitude), within the environmental studies field (just think of how damaging to the environment “innocent” – or at least apparently so – habits such as leaving the lights on when you exit a room or leaving the tap on while brushing your teeth may be).

“When we look at living creatures […], one of the first things that strikes us is that they are bundles of habits”, William James wrote in his Principles of Psychology at the end of the nineteenth century. And indeed, there are a lot of actions that we perform everyday out of habit, that is, automatically and without even knowing – in some cases – that we are doing them. Take, for instance, the morning routine of getting up, putting slippers on, switching on the coffee machine… Is this not a sequence of actions that we perform – if nothing “unexpected” happens – without being fully aware, moment by moment, of what we are doing? Since we have repeated the same gestures in the very same order so many times in the past, they have become habitual. But is then the notion of “routine” to be considered synonymous with that of “habit”? There is no straightforward answer to this question, according to many researchers: habits are not automatic or “mechanical” per se, but a certain amount of “mechanization” is proper to any habit. Be that as it may, it’s lucky – one should admit – that at least certain actions in our life get habitual, since a day without habits, in which we had to make explicit decisions about everything, would be almost impossible to get through.

Here’s some of the questions and issues that, looking at the concept of habit from the perspective of its ramifications within aesthetics, philosophy and ecology, were addressed during the workshop:

- What is a habit and what is at stake in this notion? From a philosophical perspective, how does Aristotle’s idea of habit differ, for instance, from David Hume’s or John Dewey’s understanding of it? How and to what extent are concepts such as habit, practice, routine and disposition different from each other?

- Scholars in the environmental sciences and in sociology of the environment today realize that there is “an urgent need for a robust theory of consumption that addresses how habits form, how they change and how policy can contribute to the formation of new habits that are less environmentally intrusive” (Harold Wilhite). What is an ‘environmental habit’ and why is it important? How and to what extent can “bad environmental habits” be broken and changed and, conversely, how can we develop and strengthen “good environmental habits”?

- “Reflect on what is habitual! Who could or would wish to begin such reflection?”, wrote Pierre Maine de Biran in 1802. And indeed, philosophical and analytical reflection on habits is a challenging task, also because habits “where they are stronger, they tend to conceal themselves” (David Hume). What is the potential not of philosophy, rather of literature, theatre and – with an eye to contemporary arts – virtual art installations and virtual immersive environments to “get a grasp” on our habits?

- “No act of cognition is going to change” our habits; “awareness of habit has to be cultivated at the level of sensations, feelings, and involuntary thoughts. This kind of awareness is deliberately cultivated in certain therapeutic and spiritual exercises” (Clare Carlisle) such as, for example, Buddhist meditation techniques and mindfulness techniques. How and to what extent practices such as meditation and mindfulness, which enjoy today increasing popularity, can help us become aware of our habits of thinking and acting (including our environmental habits)?

Seven speakers were invited to the workshop: Professor Jeremy Dunham (University of Durham); Professor Pauline Phemister (University of Edinburgh); Professor Marco Bernini (University of Durham); Dr Erika Fülop (University of Lancaster); Professor Andrea Pinotti (University of Milan; however, Professor Pinotti was unfortunately unable to join the workshop due to unexpected commitments); Professor Lynn Jamieson (University of Edinburgh); and Dr Harriet Harris (Chaplain at the University of Edinburgh).

The first session of the day (on “Habits and philosophy”) began with Jeremy Dunham’s paper on pragmatism and the role of the concept of habit in William James’ and John Dewey’s pragmatist philosophy (On Making our Nervous System our Ally rather than our Enemy: Pragmatism and Habit); Jeremy’s paper was followed by Pauline Phemister’s talk on Leibnizian Expression, looking at the link between Leibniz’s idea of expression and the notion of habit.

In the frame of the second session, on “Habits, aesthetics and the arts”, Marco Bernini provided enlightening insights into the potential of literature to make sense of the “awakening mind” (Literature and the Awakening Mind: Phenomenal Gaps, Hypnopompic Couplings and the Predictive Self), at the intersection between literary theory and cognitive sciences; Erika Fülop turned the spotlight on the role of the notion of habitude in Proust, with her talk Habitude, habiter, habituel: From Proust to YouTube and back.

The third session was devoted to “Habits and the environment”: Lynn Jamieson dissected the interconnections between habitual practices, interpersonal relationships and sustainability in her talk “Greening of families”: habits and practices of sustainability; Harriet Harris’s talk dealt with the relationship between habits and the environment, and how mindfulness practices can help us address our everyday habits and routines, and particularly those habits and routines potentially damaging to the environment (‘As creatures returning to their creator’: Habits, spirituality, and the environment).

This interdisciplinary workshop Habits in Theory and Practice: Philosophy, Aesthetics and the Environment left me with a feeling that the concept of “habit” has, indeed, an extraordinary potential to re-frame in an inter-disciplinary direction contemporary debates on the role of art and aesthetic experience in society, on individual responsibility towards the environment, on the interrelation between natural and cultural dimensions of human experience. In the last few years, we have witnessed an impressive growth in the scholarly interest in habits: the enthusiastic response of the PhD students, academics and non-academics who secured a place at the the workshop, and the high-quality questions that followed each talk, were further confirmations of this fact.